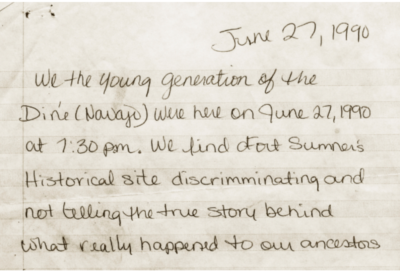

Among the world’s historic sites and memorials, Sites of Conscience stand out for their willingness not only to confront our most painful and shameful histories, but for the courage to challenge themselves to become more equitable, reflective, and inclusive spaces. In 1990, twenty students left a signed note at Fort Sumner Historic Site in New Mexico (USA) that read:

“We the young generation of the Diné (Navajo) were here on June 27, 1990 at 7:30 pm. We find Fort Sumner to be discriminating and not telling the true story behind what really happened to our ancestors in 1864-1868. It seems to us there is more information on ‘Billy the Kid’ which has no significance to the years 1864-1868. We therefore declare that the museum show and tell the true history of the Navajos and the United States Military. We are a [concerned] young generation of the Navajos for the future.”

This profound statement set the site on a thirty-plus-year journey to correct the record: The Fort Sumner Historic Site was in fact not significant for its connections to American icons like Billy the Kid, but because it was the place where approximately 10,000 Indigenous people (9,500 Navajo [the Diné] and 500 Mescalero Apache [the N’de] were persecuted and imprisoned by the U.S. military between 1864 and 1868.

In May 2022, this truth was solemnly acknowledged with the opening of the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner Historic Site. Named after the reservation where the Indigenous communities were held, today the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner documents the violations and celebrates these two cultures’ courage, dignity, resilience, and strength in the face of extreme hardship, isolation, sickness, and death.

The Coalition’s Kassidy Charles recently sat down with Aaron Roth, the historic site manager at the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Forth Sumner, and Manuelito Wheeler, an advisor to the site, to discuss the space’s evolution and its lessons learned for other Sites of Conscience.

[This interview has been edited for clarity and space. Unless where noted, all photos are from the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner taken in May 2022.]

Kassidy Charles (SoC): Could you start by telling us a little bit about the history of what happened between 1864 and 1868 at the Bosco Redondo site?

Aaron Roth: For me the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner is the culmination of several centuries of cultural miscommunications and infringement upon human rights between multiple peoples. Indigenous groups were marched here by the U.S. military – anywhere from 150 miles to 500 miles from their homes in the dead of winter. This is not a good place. It’s prone to flooding. There is no rock for mortar. You can’t drink the water; it’s salty which also makes it bad for farming. Then, when they arrived, they had to build their own shelters, dig canals, and plant fields regardless. And that is what awaited people if they survived the journey, which over a thousand did not. They had to walk upwards of 20 miles a day on foot – not reasonable for most, especially pregnant women or elderly. If you couldn’t keep up, the military would shoot you. One in five people died while at this place because of the bad conditions. So this history is about an American concentration camp.

Kassidy Charles (SoC): It seems that there are two stories here for the Bosque Redondo Memorial. First and foremost, the story of the forced migration and incarceration of thousands of Indigenous people, but also the evolution of the site itself. In May 2022, the site opened a new exhibition, ”Bosque Redondo: A Place of Suffering…A Place of Survival.” While acknowledging the difficulty of summing up a 30+ year period, how would you describe the journey from 1990 to 2022?

Manuelito Wheeler: Thirty years is a lot of time. Given the political attitude of America now, many things are changing, and this history is resurfacing. To be honest, I hadn’t seen the exhibit in 1990, although I heard plenty about it. There was something there that compelled these students to write a letter that stated, correctly, that the history of the Navajo people was not accurately represented in the space. Then, many Americans wanted to deny this, or it was hard for them to discuss. And today still, we hear the same thing. In the current American political and social scene, we are banning books, up in arms about critical race theory. But the truth will eventually come out. That’s always been the case. History evolves, and that’s why museums are important. They can put information out in a truthful way, and can validate that this is what happened. In this setting, people can have empathy for the whole situation. Over time, people get stronger and when the information is there, it’s ready to be discussed. There’s no stopping the truth from coming out.

Manuelito Wheeler: Thirty years is a lot of time. Given the political attitude of America now, many things are changing, and this history is resurfacing. To be honest, I hadn’t seen the exhibit in 1990, although I heard plenty about it. There was something there that compelled these students to write a letter that stated, correctly, that the history of the Navajo people was not accurately represented in the space. Then, many Americans wanted to deny this, or it was hard for them to discuss. And today still, we hear the same thing. In the current American political and social scene, we are banning books, up in arms about critical race theory. But the truth will eventually come out. That’s always been the case. History evolves, and that’s why museums are important. They can put information out in a truthful way, and can validate that this is what happened. In this setting, people can have empathy for the whole situation. Over time, people get stronger and when the information is there, it’s ready to be discussed. There’s no stopping the truth from coming out.

Kassidy Charles (SoC): Let’s back up a bit. Mr. Roth, can you please tell us about the history of the museum itself? When the group of young Navajo students left a note in 1990 at the site to share their disappointment and frustration, what was the site like?

Aaron Roth: That’s an excellent question. This site was developed right after 1968 – the centennial of the Treaty of 1868 – when approximately 3,000 Diné people gathered here when it was just an open field, to acknowledge this moment in history. As a result, city land was set aside and in 1970 a visitor center opened to the public. People would leave small memorial items to recognize the significance of the place, but as far as interpretation, there really wasn’t much here. Then, in May 1975, an exhibition called “Fort Sumner, an American Concentration Camp” was debuted, which – bluntly – the general public did not appreciate. It was pushed out the door almost as soon as it was installed. To put this into a bit more context, in 1986, the space’s longest running exhibit was opened with a very “cowboys and Indians” theme. The very first panel that people saw when they walked into the space said, “Newcomers to the West were met with the same ferocity from the Navajo and the M

escalero Apache that plagued the Spanish years prior.” Obviously, this really set the tone for what this space was. There was talk about the reservation, but it was very broad, and the military was there to take care of them. That was the perception.

Fast forward to 1990 when the students you mentioned arrived and were appalled by what they saw. They left the letter at the prayer shrine; a rock was placed on top of it and it was picked up by one of the site’s staff. That started a conversation and in 1990, the Bosque Redondo Memorial initiative started.

Kassidy Charles (SoC): Mr. Wheeler, in your view, what does it mean to tell a complete history? When or how does a memorial or historical site know that it has accomplished that?

Manuelito Wheeler: That’s a really wide ranging question with a lot of answers… In this case, 30 years ago, students wrote a note and started a chain of events that culminated in this new memorial. Who knows what’s going to happen 30 years from now, you know? Right now, I’m thinking like, wow, we are finally telling the Navajo side of the story, but maybe 30 years from now, another group of Navajo people are going to say there’s even more information to share. I’m not sure we can ever say we’ve 100% gathered the whole truth; but we can openly acknowledge that these are never ending processes, and that that’s ok.

To know if we’re effective as cultural spaces, I think first, it’s vital to include survivors and descendants in the creation of the space, recording their reaction – or reactions – to the history.

And then it’s, of course, also important to analyze how a non-Native museum visitor interacts with the space. Has it changed their mind a little? Have their feelings and emotions been engaged, affected? That’s how you know if the story is on the right path, and this exhibit is heading, guiding people in the right direction. That’s what museums, historical exhibits, and memorials should be about.

Of course, there’s no way such a place or a Site of Conscience is going to get 100% of everyone’s support. Some people will disagree with the information shared, but if they are there in the space, there is hopefully some opportunity for connection and growth. Working inclusively requires patience and trust and ties with the community.

Kassidy Charles (SoC): Mr. Roth, what’s your view on this? What does a complete history look like to you?

Aaron Roth: The history initially told here was very one-sided. It was told from the archival perspective, which is primarily the perspective of the U.S. military, and really lacks any kind of empathy or humanistic perspective. It basically states: We did this. We did this. There was no real thought process as to how they felt about what they did. It was just an explanation of what did occur. So the fact that we had this up on the walls and this was how the history was told was very problematic and very colonial in its interpretation. We’re not ever going down that pathway again. Now, the overwhelming majority of information comes from Indigenous communities. The archival information acts as more or less a frame of context. It sets the stage, but the narrative is told through Indigenous perspectives. And, to Manny’s point, we respect the need for multiple perspectives. We don’t ever want to close our doors to a new history, a new story that’s being told. Because I can’t tell you how many times you get to talking with somebody in the exhibition and they say, “Well, yeah, this exhibition was great, but this is what happened in my family.”

Kassidy Charles (SoC): Do you have any advice for communities that are going through this challenging process of trying to tell the history of a site? How would you advise people to build bridges between different communities in a productive way?

Manuelito Wheeler: I have been involved in a lot of exhibits but there is a real difference in a genuine commitment to inclusivity and a more general adherence to it. I have been an advisor to many big exhibits about Native people that were organized by non-Native people. They would often get people like me to sit on an advisory committee, but it was still clear to me that the organizers’ minds had already been made up about the exhibit and the narrative that was going to be shared. They just wanted some Navajo people in the room to corroborate their theories, to tick some boxes. That happens a lot.

On the other hand, a truly more inclusive approach would choose consultants who will really give them honest answers that are meaningful and within the context of whatever is being explored. The people organizing these initiatives really need to be objective on the information at hand, and not just push a particular agenda. They need to be conscious not only of the information presented, but of the process of bringing that information to the public. This is the hard work, the nitty-gritty of history and historical processes, that museums and academics need to embrace.

Kassidy Charles (SoC): Mr. Roth, can you provide insight into the evolution of this particular space, as far as community involvement with both Native and non-Native communities?

Aaron Roth: How was this space developed? Initially, the state did not do a very good job. There was a lot of taking of information, but little conversation. We came to a crossroads in about 2015 when we were developing plans for the current memorial, but had to face the fact that the process did not include any kind of tribal community support. Basically, we were planning to develop the exhibit and then ask for forgiveness later, which

we could not do. Our only choice was to start over, which is what we did. We then reached out to both tribal communities to select their own representatives. We had our first meetings in 2016, but it took us about six months just to learn how to have a conversation because so much trust had been lost over the years. In order for this to be a true partnership, the State had to listen and not talk.

I’ll just give you one example. As Anglo museum representatives, there were frankly a lot of things we thought were good ideas, but from the Indigenous perspective were simply not. For instance, one of the things that we thought was a good idea was having a space to say prayers before entering the memorial. Our exhibit designers came up with this concept – there were symbolic objects coming down from the ceiling, a ceramic bowl that you could burn sage in, but generally it was a calm space, where we felt a peace could be established.

We were really proud of it, but then, you know, Manny offered his thoughts and said, “That’s a really thoughtful idea, but praying is a very private occasion in this context. It’s not something you want to like, have people walking around you while you’re trying to be in prayer. So while well-intentioned, it’s not a good idea.” So we scrapped it.

That’s why it’s so important to have the people who you’re intending to serve present from the very start and there through the whole process. If you want them to have a seat at the table, let them fill it with who they think is representing the culture of the people. Make sure that everyone who needs to be present is there from the start.

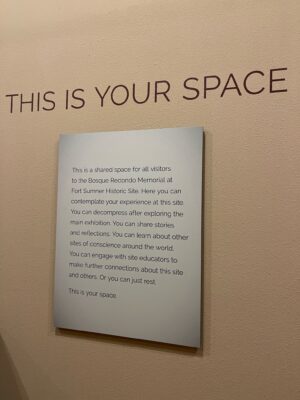

So from 2017 to about 2020, we had ongoing conversations about exhibition design and what this place could really be. In the middle of COVID, we were installing the exhibit and also recording oral histories of descendants in multiple languages so that this history could literally be told from the people’s perspective. The museum/memorial is actually a living changing exhibition, told through community voice for the first time. It’s really been quite an experience. A lot of things happened during this time, a lot of very powerful experiences and we feel as though our partnership or relationship with our tribal communities is probably the best it’s ever been. What’s nice about the exhibition is the way that it’s never going to be finished. We don’t ever want it to be finished. We don’t ever want to exclude somebody who comes in with a story that challenges this history, or has something else to contribute to it. So it’s always evolving. In fact, we’re developing an exhibition right now, which will be an add-on to our reflection room that talks about stories of healing from different communities. The takeaway is that this is going to be a continually evolving space.

Kassidy Charles (SoC): As a Site of Conscience, the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner emphasizes how relevant history is today. What are some strategies you’ve learned, as a site manager, for continually activating that prized connection between the past and the present.

Aaron Roth: One thing we try to remember at the site is that this is very recent history, history that has had a direct impact on people today. So visitors are not just hearing about hardships their ancestors went through; they’re also being acknowledged in this space for things that they went through.

Additionally, there are questions throughout all of our galleries that pose questions to visitors: What would you do if a government tried to come in and remove you from your land? What would you do to get back to your homeland? People have the opportunity to reflect and to respond to these things. They can even type them into a computer which then projects onto a wall so their answers become part of the exhibition.

Bosque Redondo is now a place where your voice is heard. You are acknowledged.

Is it enough? Probably not, but we keep trying. From a personal perspective, I don’t have any direct connection to this history, but my family history is largely Jewish German – so the themes, the feelings, the experiences certainly overlap. Most of my family were murdered in concentration camps. So, when I think about this space from an Indigenous perspective, I can see how this is a graveyard for many people. It’s another instance in history that humanity was lost and not acknowledged. We can’t just wash over these instances, lump them into a “Trail of Tears” montage. Everyone’s story deserves to be properly acknowledged. So that’s how I became involved in this project and I think it can be a way for others, from different backgrounds, to relate to. I view this history through my family who were based thousands of miles away. I think about them, and how they were just wiped out. I will never have any connection to them. I will never be able to communicate with them. I will never hear their stories.