By Alissandra Cummins,

Director, Barbados Museum & Historical Society

“History will be kind to me for I intend to write it myself.”[i] This popular quotation – often incorrectly attributed to Winston Churchill – encapsulates a conundrum over history and ownership that every 21st century historian must face. Who is allowed to write the narratives that will be recorded and remembered? Can societies and historians trust that those narratives are as multi-layered as they should be?

For the Caribbean people, these questions surfaced at a critical moment following  emancipation from slavery in 1833, but it took almost a century before someone fully articulated the complexities surrounding the “ownership of identity.” This summation came not from an historian, but from the charismatic Marcus Mosiah Garvey,

emancipation from slavery in 1833, but it took almost a century before someone fully articulated the complexities surrounding the “ownership of identity.” This summation came not from an historian, but from the charismatic Marcus Mosiah Garvey,

a Jamaican political leader who promoted the return of displaced Africans to their ancestral lands. Garvey approached the issue from an artistic and cultural standpoint. During the 17th session of the Convention of Negro Peoples of the World in 1934, he noted, “One’s civilization is not complete without [art].” Claiming proudly that, “We were the ‘first’ of the artistic peoples,” Garvey lamented that art had not been fully credited in the development of the African peoples. He also bemoaned the failure to identify and develop black artists who might equal a Michelangelo

in stature, and actively advocated for the recognition of Haitian Revolution Leader Toussaint L’Ouverture as the “greatest soldier of the world for the past 300 years.” L’Overture’s defeat of Napoleon’s military forces was never forgiven, but very deliberately forgotten from history books until virtually the 21st century.

It was explicit erasures of this kind that Garvey first addressed, and which C.L.R. James, Frantz Fanon, and others felt compelled to “re/address.” Their point was this: If you did not see “yourself” represented in art then you could not claim a history. You could not be a “people” or a “culture” as understood in the Western world, which made it difficult to claim a role in the heritage and historical development of your community and country. Within a year of Garvey’s statement the region erupted in labor riots among a population whose domestic and work conditions had not significantly changed in the previous century. The response to these events disrupted the Caribbean landscape forever.

The art historian Grant Kester has explained that, “Knowledge is reliable, safe and certain as long as it is held in mono-logical isolation and synchronic arrest.  As soon as it becomes mobilized and communicable, this certainty slips away and truth is negotiated in the gap between self and other, through an unfolding, dialogical exchange.” [ii] He finds hope in avant-garde art, which for him, “…constitutes a form of critical insight; its task [being] to transgress existing categories of thought, action and creativity…to constantly challenge existing boundaries and identities.”[iii]

As soon as it becomes mobilized and communicable, this certainty slips away and truth is negotiated in the gap between self and other, through an unfolding, dialogical exchange.” [ii] He finds hope in avant-garde art, which for him, “…constitutes a form of critical insight; its task [being] to transgress existing categories of thought, action and creativity…to constantly challenge existing boundaries and identities.”[iii]

This transgression of boundaries, this respect for fluidity, is precisely what contemporary museological and heritage practice needs today.

It is vital that we acknowledge the vast silences which existed (and to some extent still exist) within the written record of Caribbean colonial history. It has long been understood that “otherness” exists within our history and culture. But now these silences, as the Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot has delineated, need to be given an equal voice in the production of historical narratives.[iv] A dialogical process must be engaged in which oral and traditional testimony, as well as the resuscitation of memory, is given equal respect in the negotiated space of heritage interpretation.

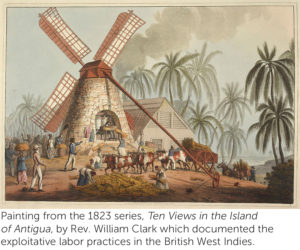

UNESCO’s current agenda for the representation of Small Island Developing States rightfully includes support for the documentation of the history of oppression in the region and its effects. This is a vital step. History needs to be represented beyond the central representation of the colonizer; it needs to embody the experience of the oppressed. We must think of history as a fluid interpretive medium through which multiple (his/her)stories can and must be told. In the Caribbean context, history should include, for instance, conceptualized rebellion, which was planned and executed within the punishing (and far more well-documented) world of the plantation economy. This would ensure that Caribbean history includes stories of self-actualization and self-realization, not only stories of manumission and rescue. Caribbean peoples must be regarded as forces effecting actions towards their own destiny.

This will require change. Heritage practice must comprehend that rather than just remain bit players in colonial actualities, Caribbean peoples must rewrite or rather, write our

This will require change. Heritage practice must comprehend that rather than just remain bit players in colonial actualities, Caribbean peoples must rewrite or rather, write our

hi(/her)stories – as the descendants of both colonizer and colonized. Doing so will ensure the region is a fully recognized culture based on both shared and unique national narratives. Rewriting history particularly in terms of dialogic and not monologic practices of museum/art/heritage production presents a critical framework that addresses the new forms of agency and identity mobilized by the process of collaborative production. As Trouillot reminds us, “History is the fruit of power…the ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.” [v] We must be prepared to accept this challenge to expose the roots of history if we believe that black lives really did matter.

Alissandra Cummins, a distinguished member of the Coalition’s Ambassadors Circle, was named President of the International Council of Museums in 2004, after serving as Chairwoman of the Advisory Committee for six years. A recognized authority on Caribbean heritage, museum development and art, she is the Director of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society and was elected a Fellow of the Museums Association (U.K), a first for the Caribbean.

[i] Churchill in a speech delivered in the House of Commons on January 23, 1948 actually stated, “For my part, I consider that it will be found much better by all Parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history.” Churchill was by then the leader of the opposition party, his Tory government having been defeated in the elections of 1945. Not coincidentally, in 1948 Churchill did begin literally writing history.

[ii] Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many – Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context, Duke University Press, 2011, p.19.

[iii] Kester, p.20.

[iv] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Beacon Press, Boston, 1995, p.147.

[v] Trouillot, p.xix.