COVID-19 is impacting all aspects of our world, including the fields of culture and heritage, in countless ways. Indeed, from art galleries in France to historic sites in Senegal, the “museum world” is one of the most affected sectors across all societies, with almost every museum and historic site in the world currently closed to the public.

In response, many Sites of Conscience have begun to ponder not only how best to adapt their platforms during this new normal, but also to consider what this period might teach us about the role of memory and physical sites going forward. How has this crisis reaffirmed or altered our ideas regarding the power of place? What will we carry forth from this time – logistically, thematically, emotionally – and what will we happily leave behind?

There, of course, is not one single answer to these questions; indeed, the exploration of our options from multiple perspectives is core to how we approach change and growth at the Coalition. Here we bring together two different viewpoints on the role Sites of Conscience can play in this new environment and its wake – one from Monte Sole Peace School Foundation in Northern Italy, which experienced one of the earliest and most devastating COVID-19 outbreaks, and another from Gulag.cz, a member in the Czech Republic that documents Soviet labor camps and has long relied on virtual platforms to reach its audiences.

A Site of Conscience in Quarantine: An Advocate for Diversity and Experience

Monte Sole Peace School Foundation, Italy

The first Italian decree came into force on February 21, 2020 – making Italy the first country outside Asia to issue a national lockdown in response to COVID-19. Until recently, the country was the hardest hit nation after China in terms of infections and deaths, and it has experienced increasingly strict limitations regarded health protections and confinement in the last several weeks. Like many museum and historic site practitioners, we at Monte Sole Peace School Foundation have found ourselves relying on digital archives and virtual collections during this time, which naturally made us reflect on the role of Sites of Conscience now.

On a very basic level, as we see it, it is exceedingly important for Sites of Conscience to continue doing during  this crisis what they always aim to do: invite communities to reflect and participate in the debates of the day with their own words, own feelings and individual stories. Only in this way can productive dialogues surface that examine the virus from a variety of angles – from scientific to political and sociological. But what is the best way for a Site of Conscience in quarantine to encourage this dialogue?

this crisis what they always aim to do: invite communities to reflect and participate in the debates of the day with their own words, own feelings and individual stories. Only in this way can productive dialogues surface that examine the virus from a variety of angles – from scientific to political and sociological. But what is the best way for a Site of Conscience in quarantine to encourage this dialogue?

Like many in our field, we at Monte Sole have been asked to lead some workshops online or through other virtual spaces. In many ways, it seems to make sense: such technology is widely used and can, at least partially, compensate for the lack of physical socialization today. Nevertheless, after considering such workshop requests, we decided that we could not participate with our communities in this way. This is partly because of the value we place in the physical site of Monte Sole Peace School itself. The site is located in a natural and historic park that is scattered with the ruins of former villages that were destroyed by Nazi SS troops with the help of Italian fascist elements in 1944. During this rampage, which was conducted in just one week, 800 people lost their lives.

When we refer to our work, we do so as an experience. For us, the site must be experienced, and not only through what one sees and hears. Above all, for us, Monte Sole is about what you feel when visiting the site and interacting with other participants on that visit and their feelings. Each workshop is designed considering the needs of the group. Participants are the starting point of our methodological approach, and, consequently, following the flow of what emerges from the group itself during the workshop, the path also adapts to the needs and requirements expressed. The knowledge of the historical processes, events, and protagonists of 1944 serves as a stimulus for a deep reflection on the mechanisms that led to those events. The educator, through interaction with the participants, raises doubts and questions about the dynamics of human actions, encouraging examples directly taken from everyday life. In other words, during our in-person workshops, the full experience is essential, and as we see it, this simply cannot be recreated in a remote mode.

Recreating this feeling in a virtual setting is difficult in part because social media and other virtual platforms are so often about one’s personal views and opinions. You get newsletters from who you want. You follow Facebook pages of sites and people you like. You create a sort of idea of the world, but it is a world that is only partially real because it tends very often to be one-sided and reflective only of your experiences, likes and dislikes. Ideally, however, Monte Sole as a Site of Conscience inspires another world altogether – one that puts you smack dab into a different experience. Monte Sole reminds us that we are diverse, that there are other needs apart from ours and that we should care about them. At this moment, we are focused on reminding our community of that – and, for us, there is a vital and emotional role in keeping our community together by reminding them about the work waiting for them at the site. There is an irrevocable role Sites of Conscience can play in this new normal by helping communities to keep this need for diverse experiences alive while our physical interactions are limited.

Recreating this feeling in a virtual setting is difficult in part because social media and other virtual platforms are so often about one’s personal views and opinions. You get newsletters from who you want. You follow Facebook pages of sites and people you like. You create a sort of idea of the world, but it is a world that is only partially real because it tends very often to be one-sided and reflective only of your experiences, likes and dislikes. Ideally, however, Monte Sole as a Site of Conscience inspires another world altogether – one that puts you smack dab into a different experience. Monte Sole reminds us that we are diverse, that there are other needs apart from ours and that we should care about them. At this moment, we are focused on reminding our community of that – and, for us, there is a vital and emotional role in keeping our community together by reminding them about the work waiting for them at the site. There is an irrevocable role Sites of Conscience can play in this new normal by helping communities to keep this need for diverse experiences alive while our physical interactions are limited.

Reminding people of the need for these real experiences in the future can be a beneficial exercise for Sites of Conscience right now, and can encourage the spirit of open debate every healthy democratic society needs. If we share information and recommendations through social media and other virtual channels, we should make it clear that every context is different and that one decree affects the many sectors of society in diverse ways. Regarding the pandemic, we can at once acknowledge that we are united in ending the spread of the virus, but also acknowledge that this results in an array of complications in other contexts. By doing this, Sites of Conscience can support their audiences by making them conscious and active not only about the pandemic itself, but about other challenges wehave faced, are facing, and will face in the future.

In conclusion, a Site of Conscience in quarantine can be a place that does not give reflection up. As one of our friends in Egypt recently shared with us, this is a moment in which it is constantly repeated that we can all be potential killers. If we pass the virus to the vulnerable, we can kill. As a Site of Conscience, we must remind each other that this has always been true on many different levels: our decisions, our behaviors, our votes, our vices. We should take this experience as the vivid reminder that we can be, at the same time, the victim and the perpetrator, not only during a pandemic but in our everyday lives.

Be Online with your Museum, or What to Do During the Coronavirus Crisis

Stepan Cernousek, Gulag.cz Association

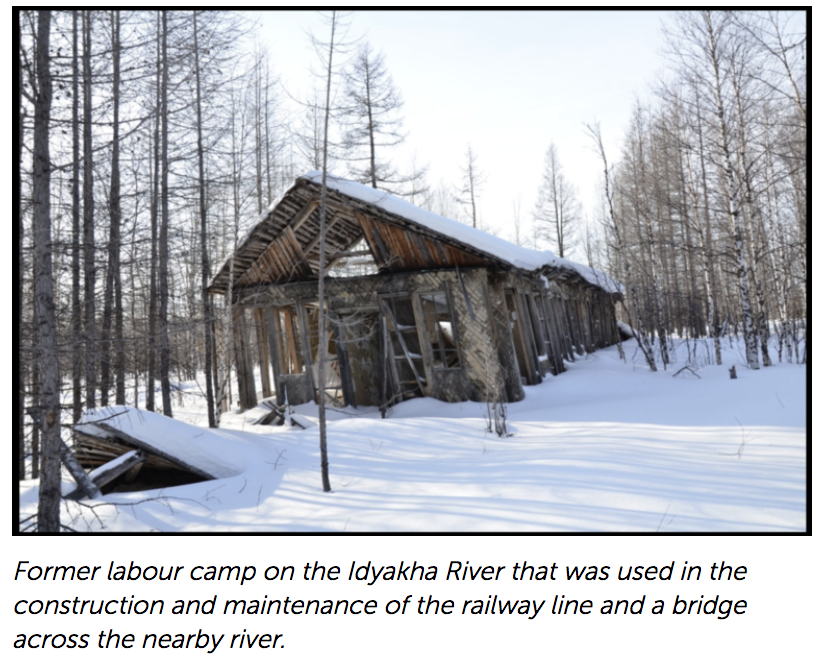

How can historians and activists show places to people when access to them is limited? At Gulag.cz, where our mission is to document abandoned Gulag camps in Siberia, we have been dealing with this challenge for more than a decade. For one, it is physically challenging – to put it mildly – to reach these camps, scattered as they are in remote parts of the Siberian wilderness in varying degrees of preservation. For this reason, it is not well-populated. There are no school excursions to the Siberian wilderness; the most common visitors to the region are local hunters and fishermen. In addition to its physical inaccessibility, there is very little political will to document these sites and the stories they hold.

But the abandoned Gulag camps are of unique historical value and, if properly documented, can shine a light on one of the darkest chapters in 20th century history just as sites of former Nazi camps or Japanese internment camps do. For us, this value compelled us to explore creating virtual forms of the Gulag camps and inviting audiences to visit them online. We conducted four in-person expeditions to Siberia from 2009-2016, using the experience to develop 3D models of the camps and barracks. We initially published these on our website www.gulag.cz., and in 2016 launched a more extensive virtual museum called Gulag Online (www.gulag.online), where you can find the results of our expeditions, including 3D models ofGulag camps, but also 3D models of objects found at the camp, maps including satellite images as well as panoramic photos. The images are accompanied by dozens of stories of people from several European countries who went through the Gulag camps or were victims of other forms of Soviet repression.

But the abandoned Gulag camps are of unique historical value and, if properly documented, can shine a light on one of the darkest chapters in 20th century history just as sites of former Nazi camps or Japanese internment camps do. For us, this value compelled us to explore creating virtual forms of the Gulag camps and inviting audiences to visit them online. We conducted four in-person expeditions to Siberia from 2009-2016, using the experience to develop 3D models of the camps and barracks. We initially published these on our website www.gulag.cz., and in 2016 launched a more extensive virtual museum called Gulag Online (www.gulag.online), where you can find the results of our expeditions, including 3D models ofGulag camps, but also 3D models of objects found at the camp, maps including satellite images as well as panoramic photos. The images are accompanied by dozens of stories of people from several European countries who went through the Gulag camps or were victims of other forms of Soviet repression.

Last year, thanks to the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience and a Fulbright scholarship, I had the opportunity to visit many museums and Coalition members in the United States, including former internment camps, plantations and other sites. In all honesty, I was a bit jealous of the physical spaces they preserve and inhabit. Why bother with virtual reality when we can tell similar stories with real reality? During my visit, however, I had been sharing the next phase of Gulag Online, which uses virtual and augmented reality as another form of presentation. While I cannot say that these platforms compare to being at an actual site, I was still tremendously moved by people’s reaction to them. These technologies allow for extremely intense experiences that give people a real sense of what a Gulag camp was like and the atmosphere that prisoners were made to endure.

While no virtual space can replicate the feeling of a having a former detention center or a prison cell under your feet, it can inspire other feelings – particularly the solitary nature of so many such places. While experiencing a space with a group of people, very often strangers, certainly has its didactic benefits, so too can the best virtual reality in that it can rather uniquely recreate the meditative, alienated feelings many of those in isolation report feeling. Of course, that’s not to say you can put on a VR headset and know what it feels like to be a prisoner, but no visitor to any site – real or virtual – can truly know that. Still, each type of site, in its own way provides clues and, in doing so, fosters understanding and compassion.

feet, it can inspire other feelings – particularly the solitary nature of so many such places. While experiencing a space with a group of people, very often strangers, certainly has its didactic benefits, so too can the best virtual reality in that it can rather uniquely recreate the meditative, alienated feelings many of those in isolation report feeling. Of course, that’s not to say you can put on a VR headset and know what it feels like to be a prisoner, but no visitor to any site – real or virtual – can truly know that. Still, each type of site, in its own way provides clues and, in doing so, fosters understanding and compassion.

Our next goal as a Site of Conscience is to create a traveling exhibition and museum, along with educational tools for students. The COVID-19 crisis has shown us that children can – and sometimes must – learn at home, relying solely on online material. And what could be more interesting, particularly at this moment, than to leave your room for somewhere else (at least virtually) and learn something profound on the way? Online options also provide some financial protection against losses that may occur when physical sites are shuttered whether because of a pandemic, the climate crisis or a political change. While they do require internet access, they are also more accessible for people who perhaps cannot afford to travel to specific sites – whether it’s in their own country, another continent, or the Siberian wilderness.