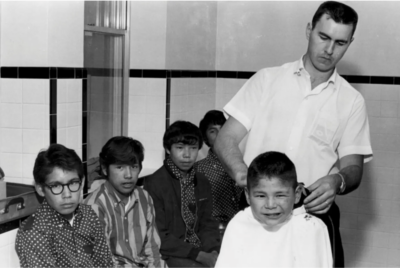

In Sault Ste.Marie, Ontario stands “Reclaiming Shingwauk Hall,” the first permanent survivor-driven exhibition dedicated to sharing the stories of Indigenous children who experienced the Indian residential school system in Canada. Funded by the Canadian government’s Department of Indian Affairs and administered by Christian churches from the 1880s to the end of the 20th century, this system of boarding schools forcibly separated an estimated 10,000-50,000 children from their families. Students were often renamed and forbidden to acknowledge their Indigenous heritage or speak their own language. In 2015, the country’s National Truth and Reconciliation Commission said the schools were a tool of “cultural genocide.”

Located at the site of the former Shingwauk Indian Industrial Residential School, the exhibit covers over 110 years of history and is managed by the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre (SRSC), a Site of Conscience and a grassroots community heritage organization dedicated to foregrounding survivors’ experiences within the larger context of colonialism, truth telling, and reconciliation in Canada. Communications Assistant Kassidy Charles recently talked with Krista McCracken, a researcher and curator at (SRSC), to learn more about the importance of community and the site’s commitment to Indigenous-driven, decolonized history practice.

For readers who may be unfamiliar with this subject, can you please start by telling us the history of residential schools for Indigenous children in Sault Ste. Marie?

Krista McCracken: The Shingwauk Residential School operated from 1873 to 1970 in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada. It was operated by the Anglican Church of Canada and the Canadian government. Like residential and boarding schools across North America, it was designed to take away the language, culture, and identity of First Nation, Inuit, and Métis children. Children were separated from their families and sent to Shingwauk from across Ontario, Quebec, the Western Canadian provinces, and the United States. Residential schools caused immense intergenerational harm to many Indigenous families and communities. Today, the Shingwauk Residential School site is home to Algoma University and the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre. Guided by residential school survivors, the Shingwauk site looks to educate people about the legacy of residential schools and actively reclaim spaces for the community.

Many photos of children have been released by the Catholic church. Some of these pictures are the last photos that families have of other family members. Researchers are now using these images to figure out the identities of the children. Can you speak to the significance of this?

Krista McCracken: Photos have immense power to connect to community, family, and individuals. Since the early days of the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre we have been working to connect photographs back to communities and individuals. Photographs can be part of individual, family, and community healing journeys and be a starting point for important conversations. These photographs can also be part of the formal historical record and education which aims to make sure people know the truth about residential schools.

The Catholic church has paid millions of dollars in reparations and the Pope has apologized for crimes committed by members of the church. This has garnered much international news coverage, but it likely stirs up many different emotions for the survivors themselves. Can you describe some of the ways that survivors you have worked with have viewed these public acts of contrition?

Krista McCracken: Numerous church organizations and governments have formally apologized for the harm done by residential schools. For example, the United Church of Canada apologized for its role in residential schools in 1998; Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized for Canada’s role in residential schools in 2008; and most recently the Pope apologized in 2022. These apologies mean a lot of different things to different survivors, communities, and Indigenous people. Some people have welcomed these formal words as a first step and others have called for more tangible action to be taken by these organizations. There is still a lot of work to be done to create right, respectful, and meaningful relationships going forward.

In addition to your current exhibitions, one goal of the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre is to incorporate more narrative storytelling and visual art into your programming. Could you tell us a bit more about these plans, and how the organization hopes they promote justice and healing in the community?

Krista McCracken: For many years narratives about residential schools were told exclusively by the churches and the government who operated the schools. Since 1981, the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association – survivors and their descendants from the Shingwauk School – have been working to ensure that their voices are centered in the telling of the Shingwauk site history. This is an incredibly important distinction and is part of what makes the exhibitions at the Shingwauk site so powerful: they are the words, voices, and the narratives of survivors and communities. Additionally, the next phase of the “Reclaiming Shingwauk Hall” exhibition works to contextualize residential schools in the larger history of colonialism. It does so through narratives as well as art. Art has the power to provide insights in a different way to engage learners of all ages and offer opportunities for participatory learning. On the Shingwauk Site, one of the next steps is the development of a new space for the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre – one which is larger, more culturally appropriate, and continues to serve the community.

In recent years, new technology has led to the discovery of human remains – mostly children – in unmarked graves at many schools. Many, if not most of their identities may never be known. How can the survivors from these residential schools play a meaningful part in telling not only their stories, but the stories of those who may not have a voice to share theirs?

Krista McCracken: Like many other former Residential School sites, the Shingwauk Site is undergoing a site search for unmarked burials. This search is being guided by ceremony and the wishes of survivors. At Shingwauk, we are continuing to work to identify all of those who attended the School, including those who didn’t make it home. Even finding out a single name that wasn’t known before can have a huge impact on a family. This work to give voice to the past involves archival research, speaking with the community, and recording community memories.